I was invited to join a panel for a Digital Exclusion event at The London Office of Technology and Innovation (LOTI). During the Q&A the panel was asked the question: As more AI gets used how do we protect human connection? It’s something I’ve been wrestling with and I did attempt at an answer but wanted to get some thoughts down. And here they are…

A system working hard but under capacity

What gets measured matters, but not everything that matters gets measured or can be measured. Often, waiting times and numbers of GP appointments are the focus to improve the NHS. These metrics define performance and shape incentives. They are important but many are largely transactional, providing only part of the picture of the health and care service. Equally important are aspects like experience, outcomes, and the feeling of care. The measures show the workforce is working hard to deliver more appointments, but there are persistent long waits and increasing public dissatisfaction indicating NHS capacity is insufficient to meet population care needs. This workforce capacity gap is not unique to the NHS, many healthcare systems globally are struggling with having sufficient workforce to meet care needs. It is in this context that we see increasing interest and effort in the development of AI tools to address NHS and social care capacity gaps. Over the next decade, we will likely see health and care system that has normalised the use of AI for multiple different parts of care services.

What we measure matters because these metrics and incentives also drive the development and implementation of technology like AI. If the metrics and incentives focus on transactional measures of healthcare what happens to human connection and the feeling of care when services become increasingly underpinned by AI tools? Who decides which metrics will matter?

Increasingly capable AI tools

AI tools are being developed and used for cancer detection, detecting haemorrhaging, and in eye screening to detect diabetic retinopathy. More recent leaps in AI capabilities have lead to AI scribes being used to capture medical notes and an AI tool that is now approved for autonomous use to detect skin cancer. Many of these tools aim to save staff time, and some, like AI scribes, can enhance clinician-patient interaction. However, there’s also emerging AI tools could soon be a replacement for human contact.

Generative AI tools in the form of chatbots show promise for triaging and decision support, and answering questions. The NHS has been trialling AI to replace nurse-patient calls following cataract surgery, the tool automates the conversation around patient preferences in order to assess the procedure, determine if additional care is needed, or if the patient can be discharged. Generative AI is enabling the creation of proof of concept AI therapists and behaviour coaches with positive patient experience. However, these tools are far from perfect - errors, variable information completeness and potential bias are just some of the current problems limiting their use.

How these tools improve will determine how and where they can be used. If they simply get quicker, they will still need human oversight, but if they become more accurate and address any bias, we could see care delivered without human oversight or involvement in the future.

More healthcare

The combination of increasingly autonomous AI use driven through measures based on transactional aspects of care could mean heading toward a future healthcare system that only responds to what can be tracked, ignoring what can’t. However, that’s not the full picture. We also need to acknowledge something else: AI opens up opportunities to provide care where there is not enough.

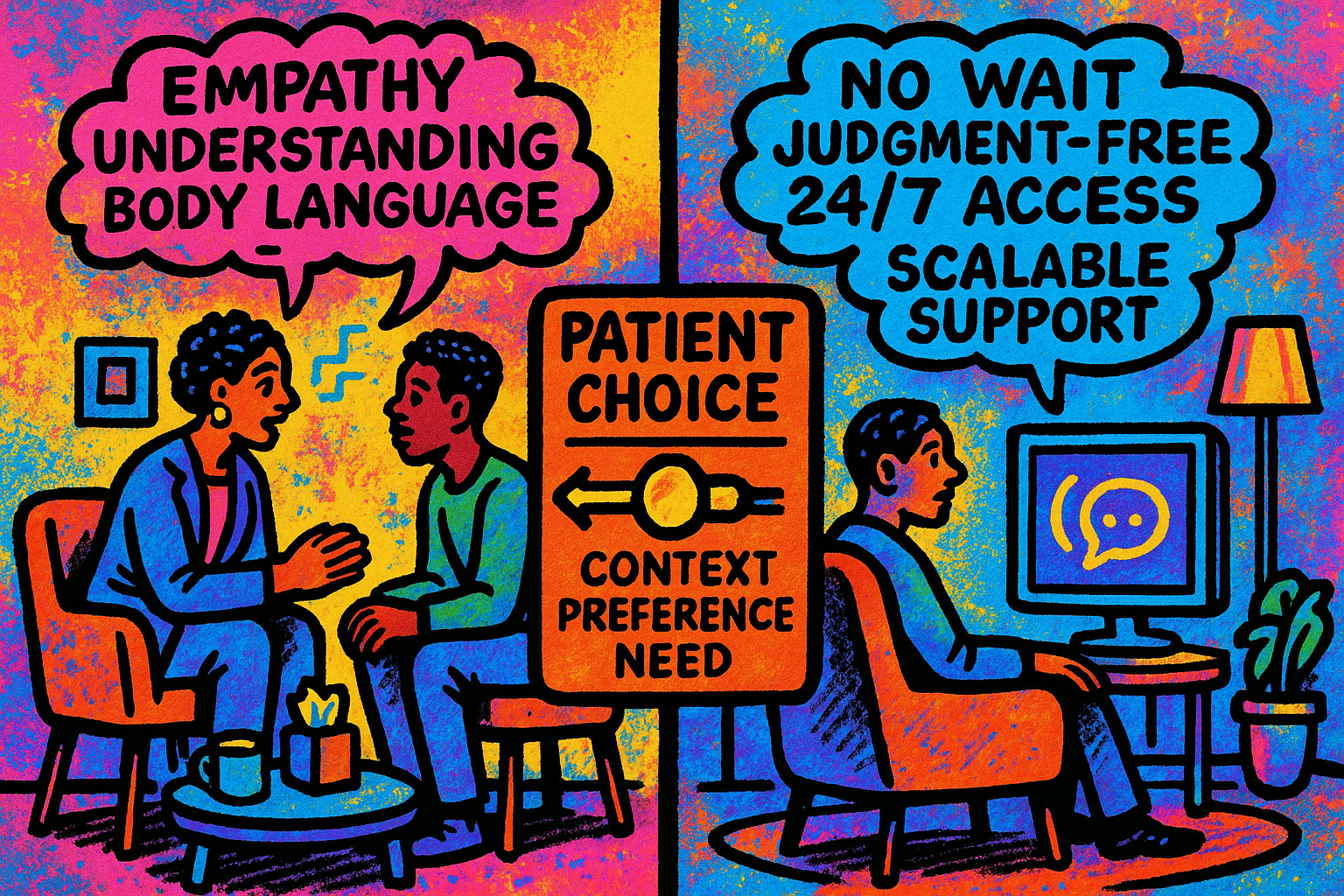

As mentioned above, the reality of the NHS, and many healthcare systems, is they have unmet needs. People aren’t getting care because there isn’t the capacity or accessibility to meet their needs. If AI is used in these cases, it isn’t replacing human care; it’s stepping into a void. If your healthcare needs are already being met (even just adequately), the idea of AI replacing your GP or therapist might be alarming. But for those not getting any help, finding services inaccessible, or facing long waits, AI might be the best option available. That doesn’t mean we lower the bar. AI tools need to be evidence-based, designed responsibly, and subject to proper oversight. But they could provide much more care in systems that are unable to meet the need – from post-op check-ins to additional AI therapy between therapist care appointments perhaps in the middle of the night when services are closed.

So, here’s the real tension: if someone is currently receiving no care or delayed care, is AI-delivered care a step up? That’s the question we need to ask because framing the debate as AI versus human care isn’t the reality of healthcare services with the workforce, accessibility and funding constraints they face.

There’s a temptation to push back and say that AI without human involvement is cold, clinical, and lacking empathy. And to be clear - human connection does matter. However, not everyone wants human care every time - patients do avoid care when they fear judgment or stigma. And if the alternative to AI-enabled care is delayed care or no care at all, it becomes harder to argue that the presence of AI is inherently unethical. Having something that’s safe and effective may be significantly better than having nothing.

Rather than simply asking whether AI is as good as human care, we need to ask: Can it improve on care gaps in a way that’s safe, ethical, and effective?

Another important consideration is: who gets to choose where human connection is protected and prioritised? Right now, access to care isn’t always a matter of preference; it’s often determined by what people can reach, afford, or navigate. That’s not a fair playing field. The choices need to be genuine, supported, and developed with people and communities. People should be able to move from an AI to a clinician when they need to or want to. These preferences will likely change as familiarity with AI tools grows in various aspects of people’s lives – so we need a continuous dialogue.

Ongoing dialogue should help to shape how AI and clinician care blend to support equity in health experience beyond transactional metrics. Are people able to engage with the care they receive? Do they understand it? Do they feel heard, even if the “voice” is digital? Are outcomes improving in communities that have traditionally been underserved? How do we meaningfully show how AI performs compared to clinicians?

These questions might not have easy answers, but they’re some of the questions we need to be asking. AI isn’t going away, and it shouldn’t if it can play a role in expanding access and improving care. Its introduction needs to be thoughtful, with real attention to context, values, and the fact that care is not just a transaction – person to person care will continue to be valued and needed.

Providing AI options instead of clinician care isn’t necessarily a bad thing, there could be more empowerment and more care for the individual at the cost of the human connection, it could even be a better experience then what some people currently have. AI brings with it the opportunity to reduce gaps in care for those who find existing healthcare services difficult or insufficient for their needs. That's why it's important to not make assumptions but to work with people and communities to understand how AI and clinician care options come together to meet individual care needs, expectations and experience of care.

You made it to the end!

Hopefully that means you enjoyed this post, if so please share with others and subscribe to receive posts directly via email.

Get in touch via Bluesky or LinkedIn.

Transparency on AI use: GenAI tools have been used to help draft and edit this publication and create the images. But all content, including validation, has been by the author.