This week, the Labour government announced NHS Online, a national initiative to create a “virtual hospital” scheduled to launch in 2027. The idea is straightforward: patients see their GP and if they are referred for hospital care, patients will be able to access specialist care virtually through the NHS app. Alternatively they can decide to stay with their local hospital. Patients will also have the freedom to choose when and where to have their scans, tests, or procedures.

In principle, it’s a promising idea, but as ever the details are crucial to success. NHS Online could make accessing hospital and specialist care much easier, particularly for those with caring responsibilities, irregular working patterns, or face difficulties travelling or in noisy environments. A national online hospital could help overcome these challenges as long as it is tailored to individual needs and improves on what we have today. For example, remote GP appointments are fantastic but not when you have to scramble out of the shower to answer the call.

It’s important to remember there is genuine potential here to reshape how care is accessed and experienced. That’s not to say it’s without challenges. Who will staff this virtual hospital? Especially considering the current long waiting lists, is there enough staff capacity to make this virtual hospital work? To make it more likely to succeed rather than being limited by the capacity of their local hospital patients should gain access to a national pool of clinicians, with remote engagement we are no longer constrained by geography. This could allow for greater flexibility and a larger pool of clinicians to staff the hospital.

Yet, realising an idea with such potential and turning it into a functional, equitable service means addressing longstanding challenges that have plagued the NHS for decades. Key issues include data sharing, NHS app functionality, digital exclusion, and communicating with the public to shift culture.

The Data Problem

For NHS Online to succeed, clinicians must have access to complete and accurate patient information, without requiring patients to repeatedly recount their medical histories. This can only happen if data flows across the entire health system. Data sharing within the NHS has been inconsistent and problematic for years. It’s not all bleak! There has been local progress with Shared Care Records and data-sharing partnerships, but these solutions are often limited to specific geographies or small networks of providers. Similarly, the case studies on which NHS Online are based are encouraging but they remain locally bound. A truly national system will require secure and integrated data flows which has long proved politically, technically, and culturally difficult. Scaling data sharing to a national level is a challenge not to be underestimated! The instinctive response might be to rely on the still-nascent single patient record, but that also creates too much dependency on a still unclear initiative risking delays and failure. Absolutely the single patient record should ultimately enable this data flow but there needs to be a concerted effort to overcome the barriers not assumed it’s solved elsewhere.

The App dependancy

The NHS app is another obvious weak point. Currently, it is a non-native app, essentially a website wrapped in a mobile-accessible form, which limits its usability and responsiveness. The NHS app is undergoing huge development, as described in the NHS 10 Year Health Plan. If the app is to become the main route to NHS Online, its functionality and (perhaps most importantly) it’s design must be improved so more functionality doesn’t mean more barriers for patients. It’s likely NHS Online will form part of the “My Specialist” functionality proposed in the NHS 10 Year Health plan, that would then avoid duplication and confusion.

Digital Exclusion: A Real but Solvable Barrier

Digital exclusion is a legitimate concern and should not be underestimated. There are those who are unable to access or use digital services, as well as those who choose not to. However, we know what works to reduce digital exclusion: giving devices, ensuring affordable connectivity, and providing wraparound support from families, community groups, or local services to improve digital confidence and skills. For those who prefer not to engage digitally, alternatives must remain available through public spaces such as libraries or GP practices. NHS Online development should also have sustained effort to reduce digital exclusion.

The Culture Shift

Launching NHS Online in 2027 means considering the broader social context today. The public is no stranger to taking on roles once fulfilled by professionals, for example we scan our own groceries, manage our own banking, and now, through NHS Online, may be expected to book our own appointments and confirm referrals. This “self-service” model in healthcare is not inherently a bad thing if it is designed intentionally and collaboratively it means more power and choice in patients’ hands. If designed poorly, it risks worsening access and care instead of making it better. How will the enhanced NHS app functionality be designed with people to ensure inclusive and accessible capabilities, rather than introducing additional barriers? It is essential to have ongoing involvement of both the public and staff to make the shift positive and inclusive.

Focus and Prioritisation

As always with the NHS, everyone has opinions and suggestions, but perhaps most importantly, NHS Online must remain sharply focused. It should not attempt to be everything for everyone from the outset. Targeting specific specialties and demographic groups is more likely to deliver meaningful results that can be built upon. A broad, unfocused rollout with continually shifting objectives risks failure.

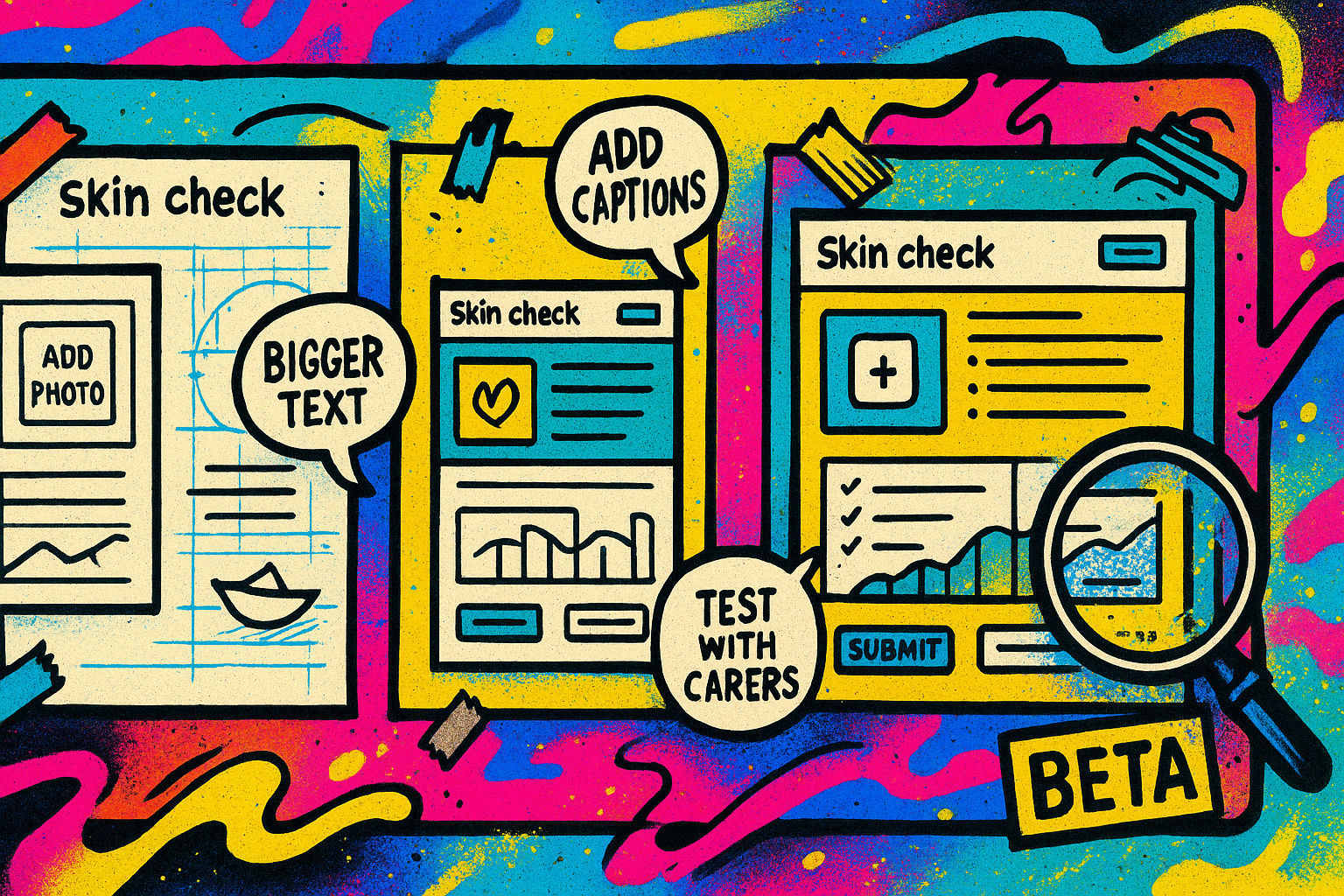

A sensible approach would be to launch NHS Online as a beta, targeted at particular groups and working alongside them to improve the service. And only then expand iteratively to widen accessibility to more people while continuing to work with the different groups to continue to make improvements. This allows for real-world testing, user feedback, and ongoing improvement.

What matters is not a polished product at launch, but a service that evolves through engagement, inclusivity, and responsiveness. At its core, it should involve patients and communities throughout development and continual improvement.

Surface Change or Deep Transformation?

NHS Online proposes quicker access to specialists, coupled with self-service patient booking for scans, tests, and procedures. This all assumes there is sufficient capacity within the system to handle patient requests. The expectation is the staff will be available by pooling staff at a national level instead of relying on local capacity. But any scans, tests and procedures are likely going to need local, in-person care which remains constrained by local capacity. Specialist consultations might be quicker to access at first, but without deeper transformations in hospitals and diagnostic centres, patients could be left with little more than a shiny digital veneer over a creaking system, while still facing long waits. Unless underlying issues are addressed, the “virtual hospital” risks becoming analogous to the phrase lipstick on a pig which is the last thing we want!

I hope you enjoyed this post, if so please share with others and subscribe to receive posts directly via email.

Get in touch via Bluesky or LinkedIn.

Transparency on AI use: GenAI tools have been used to help draft and edit this publication and create the images. But all content, including validation, has been by the author.