Introduction: Digital architecture might sound dry or technical, but it’s simply the underlying technology systems, structures, and connections that allow information to move. “Yawn!” you might think, but remember it affects how staff work, what patients can do, and how newer technologies can be used. Like anything that is foundational, it’s invisible when it works well but when it doesn’t work the problems ripple far and wide. Digital architecture affects the everyday like patients needing to repeat their stories over and over, staff wasting time chasing missing information or unable to make decisions and how digital exclusion occurs. But it also affects long-term aspirations by slowing, or even halting, innovation and scale.

Without a strong, flexible, and future-ready foundation, the healthcare system can’t deliver on its promises irrespective of how good the intentions or how hard staff work .

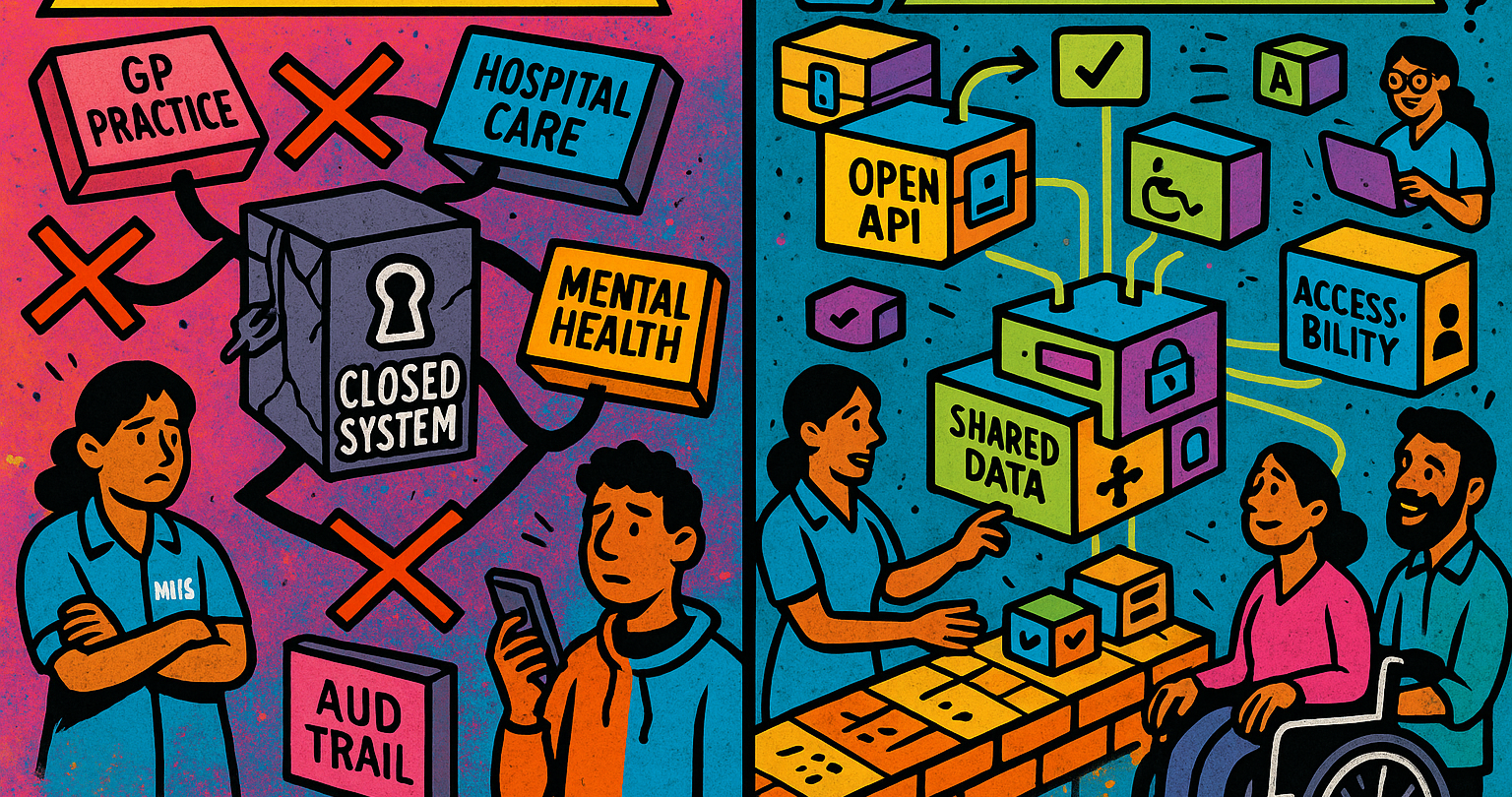

Historical Context: The NHS has been trying to digitize for decades. From the National Programme for IT (NPfIT) in the 2000s to more recent initiatives like Global Digital Exemplars, Local Health and Care Record Exemplars (LHCREs), and frontline digitalisation through modern general practice, there’s been years of investment and no lack of ambition! But many of these efforts run into the same fundamental issue: they’ve focused on individual organisations, or short-term outcomes, rather than building something truly connected and system-wide. So, we’ve ended up with a patchwork of systems with silos of data all largely incompatible due to the forms of data and the formats and structures of software. The technology we have has grown organically without sustained strategic development and design led thinking.

Impact on Care: Digital architecture isn’t an abstract technology problem. The ineffectiveness of the digital architecture overspills from the IT to affect real people every day. A district nurse who works across three different local services can’t access the patients’ full history without logging into three separate systems. Technology isn’t experienced as enabling for many staff or patients and patients can have 40 different interactions for a long-term condition no doubt feeling lost in the system.

Unreliable technology creates tech avoidance: How often does technology fail in the NHS? The answer is very simple – we don’t know. There’s anecdotal information but little robust and ongoing data is collected. This should be part of basic system awareness, unreliable technology affects staff culture and behaviours to become more sceptical about innovation and technology. It creates unnecessary pressures and wasted time. Technology fails, that is inevitable and it gets increasingly expensive to have more reliability. But a baseline understanding of the reliability and expectation should be built into the way technology works.

Keeping up with a changing world: Care needs are changing and staff have broadening interests and opportunities but the healthcare system hasn’t kept up. The demographics are changing with people living longer, there’s increasingly more people with multiple long-term conditions that need to be managed by a team of different professionals across primary care, hospitals, mental health, and social services. At the same time, the workforce is changing. More staff are working flexible, portfolio careers as trainers, researchers, or entrepreneurs or choosing a different work/life balance from full time clinical work. That means for many the old way of ensuring continuity just “seeing the same doctor” or nurse often isn’t possible anymore. We’re relying more than ever on data to hold the story together.

The technology has been built for a world that is different from the reality of how staff work and the care patients need.

Users have no choice exacerbating exclusion: The healthcare system has many different users, even just focusing on staff there’s multiple professions all with different roles and responsibilities. And there’s patients and carers, many may have similar requirements of healthcare services but many also have different requirements and different access needs. However the approach to purchasing and specifying technology is based on policy requirements and system needs - more often than not users have little, if any, choice. Suppliers get caught trying to provide one digital solution that meets the diverse needs of clinical staff, operational staff, patients and carers. Any technology developer has finite time and money this creates a quandary - do you extend functionality or do more customisation options around user needs or try do both but then go slower or lose money? Instead we should ask: Why rely on one solution for everyone, shouldn’t we have multiple solutions that are more tailored to groups so innovation and development can happen in parallel?

The architecture of our digital systems is underdefined and continues to rely on monolithic and integrated systems that are no longer suitable for how care needs to be configured around people.

A digital future needs to make 'Architecture' matter: Our architecture is holding us back and has been for some time. New tools have to be built on top of old ones, or work around them. That slows everything down, drives up costs and makes change harder than it should be. Meanwhile, decisions about what systems to buy or build are often made in silos based on organisational priorities, short-term funding pots, or policy targets, rather than what’s good for the whole system and enables individual users. Solutions have overlapping capabilities and difficulties integrating technology means the most convenient solution and not necessarily the best solution is more likely to succeed.

Digital architecture should create the basic structure of how data is stored, how software systems interact, and how new tools can be added in future.

What Do We Want Instead?: We need to move towards an architecture that’s:

- Connected: Where data flows safely between services, so patients don’t have to repeat themselves and staff don’t have to chase missing information. But data is also available to monitor the reliability, uptake and use of tools supporting research and innovation.

- Modular: Where systems can be built from flexible components, not locked-in mega-systems that can’t evolve.

- Inclusive: Where different users—whether a community nurse, a carer, or a patient—can choose and access tools that suit their needs and preferences.

- Future-ready: Designed not just for the tools we have now, but for the ones not even imagined yet.

In part 2 I explore what a future architecture needs to improve on these challenges.

Enjoyed this post? Do share with others! You can subscribe to receive posts directly via email.

Get in touch via Bluesky or LinkedIn.

Transparency on AI use: GenAI tools have been used to help draft and edit this publication and create the images. But all content, including validation, has been by the author.