This is part 2, to read about the challenges to inclusion and innovation digital architecture creates please follow this link to part 1.

Introduction: The systems that underpin healthcare weren’t designed for joined-up, data-driven care across multiple professions and organisations that we need today. So how do we fix it? We start by rethinking the architecture not just the individual technologies, but the way those technologies are designed to connect and grow.

Problems with Monolithic Systems: Many NHS organisations use what’s known as monolithic systems - they do a lot of things all in one system and for a lot of different people. In theory, they provide consistency and a quicker route to scale innovation. In practice, they often come with trade-offs: they’re hard to change, they’re rarely flexible, they don’t always play well with others. And they are better at scaling their own innovations than that of disruptive innovators. It’s like buying a kitchen where you have a giant single unit that is a fridge-cooker-sink-cupboard all together and to change one part means changing everything.

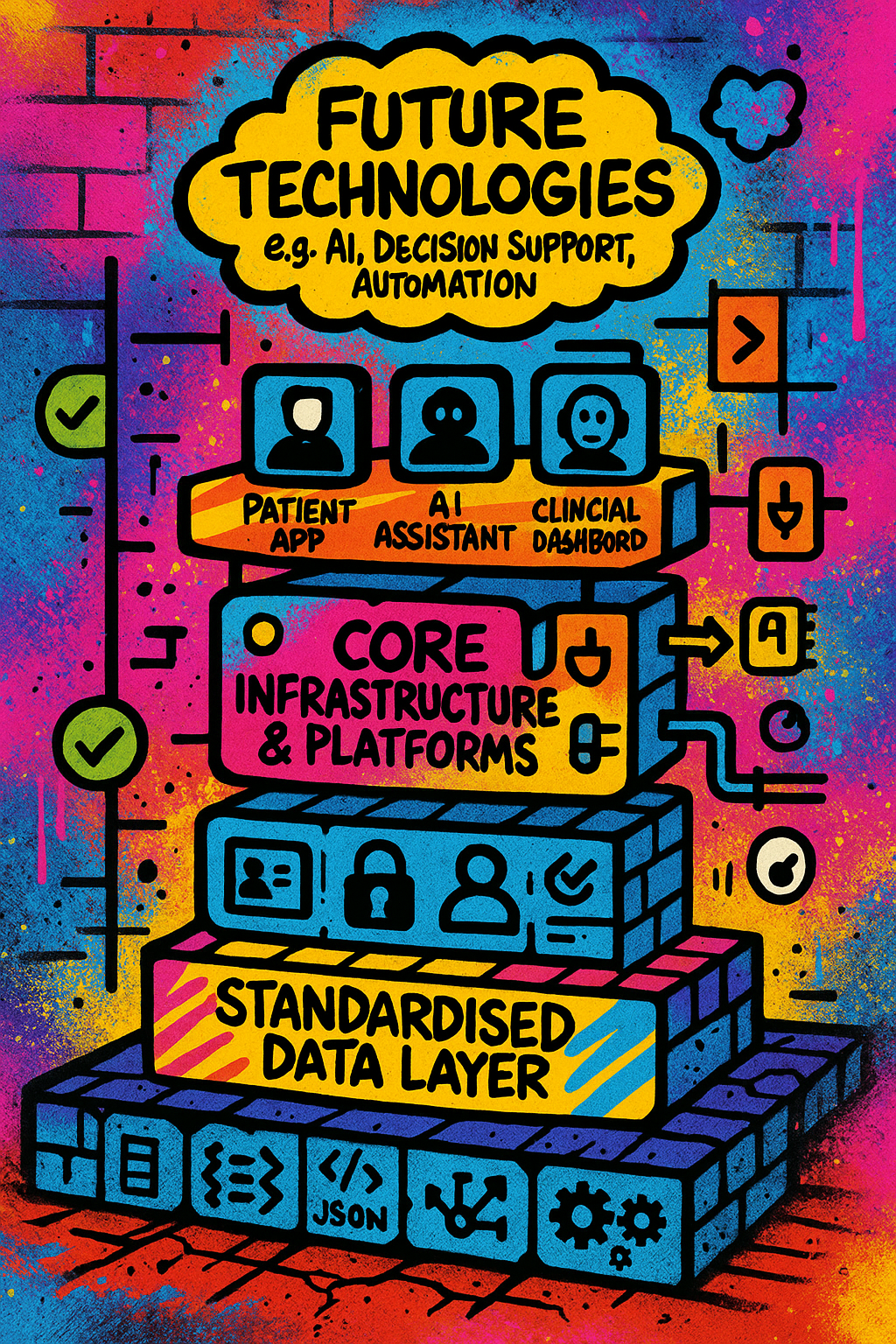

Benefits of Modularity: The alternative is modularity and it’s how most modern consumer technology is built today. A simplified version is your smartphone, it separates the infrastructure (your phone and operating system) from the applications (your apps). It should go without saying the NHS is different from a phone, with different risks and constraints but the concept of modularity could still bring substantial benefits. In the NHS, modularity would mean proactively designing and building a digital architecture based on platforms and modules structured around user needs centrally, regionally, organisationally, and individually. Such an architecture design needs to have i) core infrastructure that runs throughout, combined with ii) platforms at various levels matching the structure of the health system and all with iii) intentional module design which is meaningful for users. Core infrastructure is stable and consistent for essential and cross-cutting aspects eg identity, permissions, security, and data standards. There will need to be certain principles including: as much done at each level to enable as much efficiency and choice at the next level, slower core platforms allowing for faster innovation at the user facing application or tools level.

Interoperability and Standards: For this to work, data needs to flow freely and safely between systems. Interoperability means that different systems can share information in a common language. It doesn’t mean every organisation has to use the same software—but it does mean that data should be structured in a consistent way, with shared standards and rules. Relying on suppliers to share data adds to their costs, creates misaligned incentives to use data access as a revenue source, stop data access to protect market share and introduces delays to technology integration depending on how much resources the supplier allocates to integration. These standards need to include clinical and operational data including reliability measures which flow automatically.

Setting—and Enforcing—Standards

Data flow doesn’t happen by magic. It requires data standards—agreed rules about how information is recorded, shared, and stored.

The NHS already has some of these in place. But the challenge is that standards are often an afterthought, they are often treated as optional so suppliers won't prioritise and they need long term investment to evolve over time. Suppliers don’t always follow standards, organisations may not enforce them at procurement and there’s little national enforcement for non-compliance.

We need to change that.

Standards should be mandatory, consistent, and enforced. That means:

- Requiring compliance as a condition of procurement.

- Providing central support and guidance for implementation.

- Creating clear penalties for non-compliance and rewards for doing it right.

It also needs a layered approach of carrots and sticks to be explored from fines to deployment rights and reallocating money from fines to support new entrants. These are all ideas worth exploring.

Because without enforcement, standards are just suggestions. And suggestions are often largely ineffective.

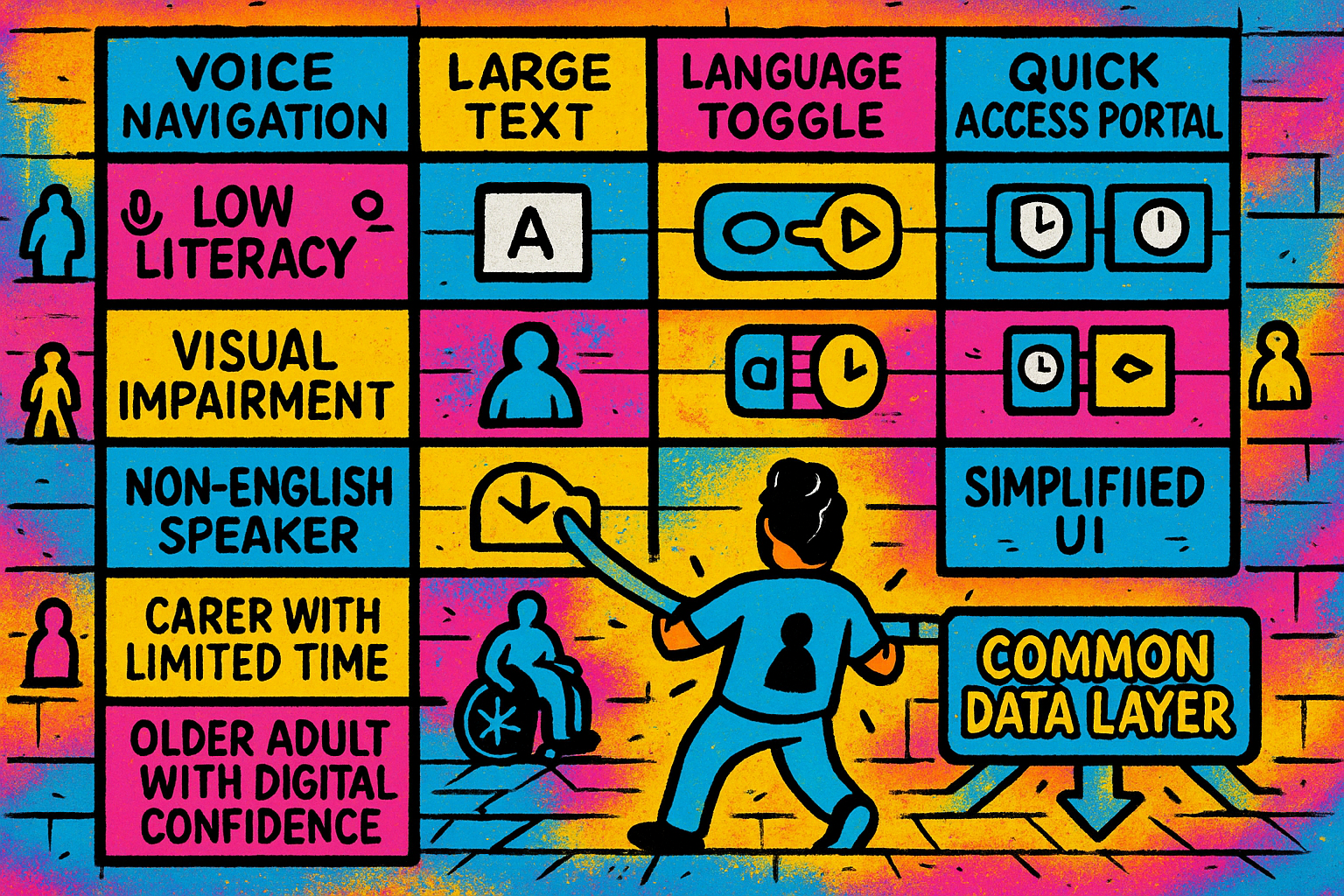

Designing for Inclusion and Flexibility: The health and care system employs people in hugely varied roles, from consultants to receptionists to carers to IT staff. One-size-fits-all systems rarely work for everyone or need considerable investment for customisation.

When systems are designed without considering differences in language, literacy, disability, or context, they don’t just become frustrating—they can become exclusionary.

Modular architecture allows us to create a different combination of tools for different users, without changing the underlying data. That means:

- Patients can access information in their preferred language or format and manage their own care needs depending on their digital and health confidence and need.

- Staff can use tools tailored to their role, without needing to learn features they’ll never use.

- Communities with specific needs—such as people with learning disabilities or those with low digital literacy—can have the option of tools that work for them, rather than being expected to fit into a system that doesn’t.

It’s about equity.

Creating Space for Innovation: It’s incredibly difficult for new digital health tools to gain traction in the NHS and social care. Significant parts of the supplier market is dominated by large, established suppliers. That’s not necessarily a bad thing as incumbents often provide essential, stable services but it can make it hard for smaller companies or new ideas to break through. With modular architecture and open standards, we can lower the barriers to entry. We can allow start-ups to build innovative modules that dock into the system without needing to replace the entirety of the system. This architecture principle can make it easier for organisations to try new tools, learn what works, and switch if necessary. It flips the top down innovation approach to bottom up. When underpinned by standardised and automated data flows its becomes possible to monitor innovation effectiveness and uptake to then create scaling through central support.

This is especially important as new technologies like AI continue to develop.

We don’t know yet exactly how AI will shape healthcare—but we do know that flexibility and agility will be essential. We can’t afford to lock ourselves into rigid systems that assume we already know what the future will look like.

Scaling in New Ways: Digital tools in the NHS often scale by geography, most often one provider at a time or in some places by networks of providers. With modular approaches we can scale differently through user preference, user need and targeted at demographics. This can potentially flip how innovation is up taken up. Imagine a patient engagement portal that could be rolled out to every patient within the country with particular cultural and language preferences rather than waiting for each supplier to address multiple and diverse needs.

Looking Ahead While We Build Today: So far we’ve looked at the current digital challenges in the NHS faced with siloed systems, monolithic software and fragmented data and begun to outline what a better, more modular and connected digital architecture could look like. But if we stop there, we risk solving yesterday’s problems rather than tomorrow’s. That means we need to build with the future in mind, not just the problems in front of us.

The Rise of AI and the Changing Role of Software: AI tools are already being used in pockets of the NHS for medical image analysis, predicting deterioration, or helping staff capture notes. Today, accessing timely and relevant patient information means clicking through multiple interfaces

But AI may soon be able to go directly to the data, bypassing those interfaces entirely.

That future will only be possible if the data is accessible, well-structured, and standardised.

If we’ve locked all our information into closed, rigid software systems, those tools won’t be developed or worse be able to be used. If we’ve chosen an architecture that assumes humans are the only users of systems, we’re limiting the role AI could play.

We need to think about building data-first architecture, not just software-first.

Avoiding the Trap of Present-Focused Planning: We don’t know exactly what tools, platforms, or practices will dominate in 10 years. So instead of trying to guess, we should build future optionality into the system. That means keeping systems open and modular. Separating the data layer from the interface. Avoiding exclusive contracts or tightly integrated platforms that prevent future adaptability.

You plan for growth, not stasis.

Here’s what a future-ready digital healthcare architecture might involve:

- A Shared, Standardised Data Layer

- Collective approach over the long term to develop and evolve standards

- Separate data and software so disruptive technologies are not dependent on incumbents

- Data should include technology monitoring to understand reliability, uptake, use and effectiveness

- Platform and Modular Applications Layer

- Platforms at different layers of the system with each able to move at a different pace. Underpinned with the principle of doing what can be achieved at one level to enable more choice at the layer below.

- Different tools can plug in and out based on user needs and preferences without changing the data underneath.

- Federated Identity and Access Management

- Staff and patients can access the right data, securely, from wherever they are, without switching between systems.

- Roles and permissions are centrally managed but flexible across organisations.

- Embedded Governance and Safety

- Data use is logged, monitored, and controlled with clear audit trails.

- Privacy, ethics, and information governance (IG) are built in with patient control.

- Support for Iteration and Innovation

- There’s space for new ideas to be tested safely through sandboxes, test environments, and structured feedback loops.

- The system is designed to evolve, not ossify, through data flows that gather evidence and insight on how well technologies perform and spread.

Who Needs to Be Around the Table?: Getting this right isn’t just a job for IT teams or national digital programs. We need technical architects, clinical leaders, information governance experts, designers, accessibility specialists, patients, and the public alongside suppliers and innovators.

And we need to create career pathways and roles for people who will help build and use these systems.

Laying the Foundations for a Better NHS: We talk a lot about building a better NHS. But we rarely talk about what it will stand on. Digital architecture is that foundation. It is time to take it seriously—not just as an IT concern, but as a core part of our vision for the future of health and care.

Enjoyed this post? Do share with others! You can subscribe to receive posts directly via email.

Get in touch via Bluesky or LinkedIn.

Transparency on AI use: GenAI tools have been used to help draft and edit this publication and create the images. But all content, including validation, has been by the author.