The single patient record is a part of the English government’s vision to modernise healthcare. While it's a simple concept, having a patient’s complete health information into one accessible platform and connected to the NHS App, the realisation is a complex challenge involving technology, governance, trust, policy, and purpose. There’s limited clarity on what it is, at one extreme it could be a collection of AI tools that summarise various different data silos at the other end it could be a single data repository for all the data for an individual. These are obviously very different!

In the early steps toward creating more clarity, NHS England issued a Request for Information (RFI) to gather insight. This RFI provides the most coherent frame to date of what the single patient record should be achieving.

Three aspirations

The RFI outlines three core aspirations for the single patient record:

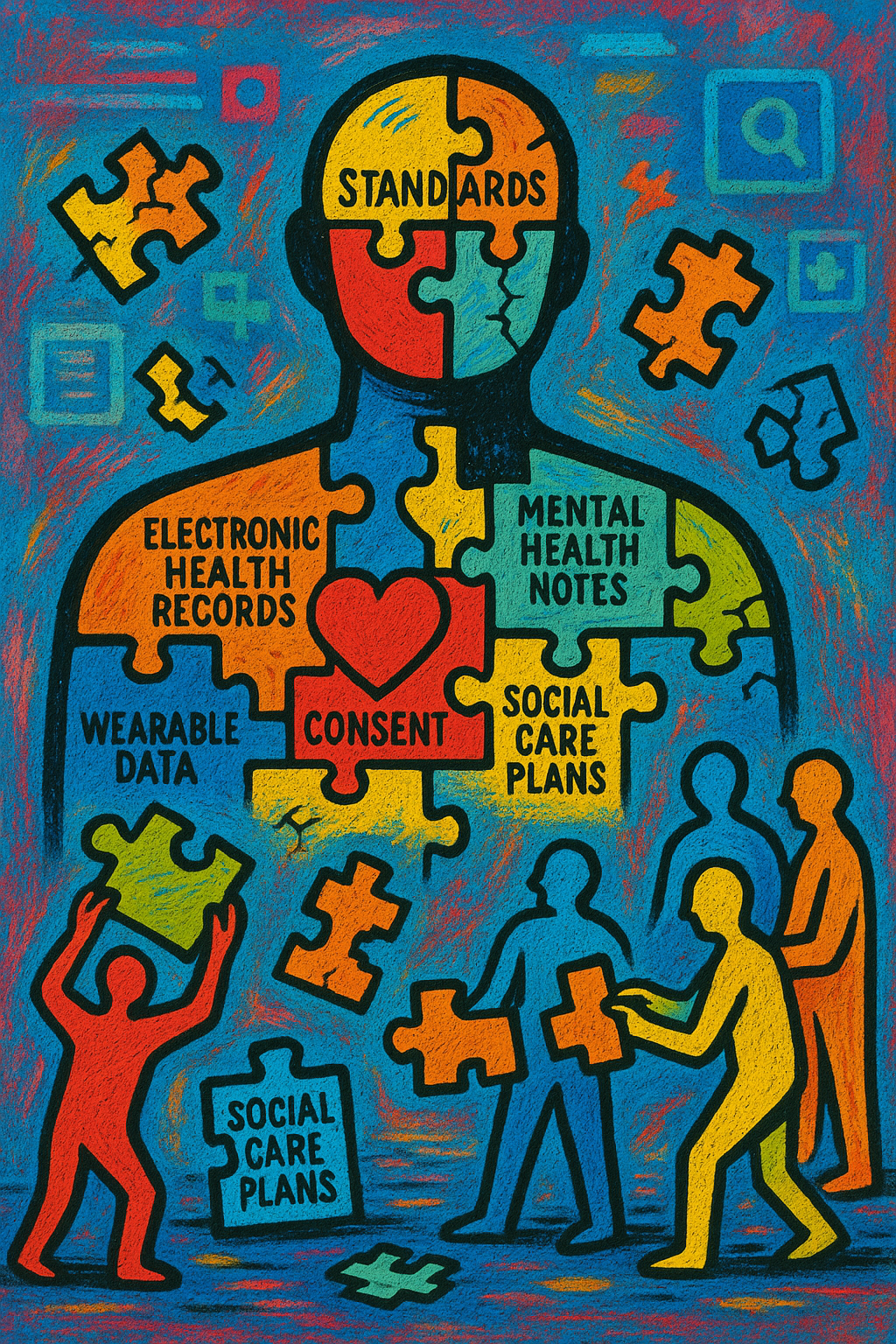

- Patient empowerment: Individuals should have visibility and control over their own data. They must be able to view, edit, correct, and share information (including care plans) and have transparency on who has accessed their record and why. This is a radical shift from the current model, where patients are often the subject of the data but with little control or visibility of the data.

- A “single version of the truth” for care teams: Clinicians across the NHS and social care should work from one unified, up-to-date record. Today, information is fragmented across general practice, hospitals, community care, and social services. This siloed data environment leads to duplication, inefficiency, and even harm.

- Patient-approval of data use for research and innovation: Health data is vital for recruiting clinical trial participants, studying population health, and developing AI-driven diagnostics and therapeutics. Trust, consent, and governance are important but challenging can this initiative make informed consent simpler?

The Problems Users Face

Across the NHS and social care, different users have different needs. For clinicians, the lack of a single record can hinder decision-making, delay diagnosis, and create lengthy handover requirements. GPs can hold additional concerns because they are legal data controllers ( responsible for the collection, storage and use of the data) and so can be reluctant to include information in the records they have not created or validated. For patients, repeating health information is the norm, leaving them with a fractured and frustrating experience. Social care professionals lack easy access to relevant clinical data, and researchers often face delays or legal hurdles in accessing anonymised, useful datasets.

Currently, the NHS has multiple data storage tools and data-sharing capabilities (e.g., summary care records, shared care records, patient-held records, and GP or hospital-based electronic health records), yet the problems outlined above persist.

So, despite all these technological solutions why do the user challenges persist?

Thinking Beyond Technology: A Systems Challenge

Technology alone won’t solve the multiple challenges users face. Looking at historic lack of success, continued challenges and progress in other countries, technology may be the easiest part!

Under acknowledged barriers are:

- Governance: Who is accountable for the integrity and use of data? How is liability distributed to enable responsible data sharing while avoiding liabilities on GPs?

- Legislation on data standards: Without legal clarity and mandates for data standards and sharing, progress will stall. The US, Denmark, and France have used legislation then enforcement through fines, payment and certification requirements.

- Culture: Data sharing must be seen as safe, valuable, and routine, not risky or burdensome. This takes engagement with professionals and the public.

- Leadership and education: Clinicians and staff must be engaged and trained to use new systems effectively and have equivalent interpretation of data sharing requirements.

- Transparency and trust: Patients need transparency and control over how their data is used, and how to control it.

These must be embedded into the design and deployment of the single patient record from the outset.

Before reaching for more technology, we need to:

- Understand what problems technology can solve

- Identify where technology is not the right tool but apply other approaches

- Have sustained long-term focus on the problem to be solved and the bite-sized steps to making it achievable

- Avoid over-engineering a solution that makes it destined to fail

So, What Is the Single Patient Record For?

This is the essential question. Is it to reduce duplication? Empower patients? Enable advanced analytics? Improve safety? It could aim to do all of these, but do we really need a new technology for these?

The single patient records is also an opportunity to break from past technology constraints and create green fields of digital capability to build a future person-centred healthcare system upon. Unless it does something fundamentally new and better than existing tools, the risk is it becomes yet another layer of digital complexity when what we need is a radical shift.

For example, one vision is that the single patient record becomes a refined, high-quality dataset which is the “ground truth” of a person’s health. Not everything goes in, but everything confirmed and essential is there: clean, validated, current, and usable. This would enable AI tools on the top which could: help clinicians by acting as data assistants, support patients manage their own health with digital interventions, rapidly identify the most suitable medications, create digital twins for prediction, and enable researchers to innovate responsibly.

A different approach would mean:

- Integrating clinical data with less familiar data types: wearable devices, at-home testing, shopping behaviours, physical activity, diet

- Anchoring data legislation around the individual

- Incentivising and supporting data quality improvement

- Creating mechanisms for AI tools to access and use the high quality single data record

Not all data needs to be stored as part of the single patient record (e.g., medical images, referral letters, etc.), in which case existing data systems would continue to exist.

The goal should not be to replace all current systems but to dual-run and gradually shift toward a unified data layer that supports personalised, intelligent, equitable care.

Building It Right

To minimise delays and get the most out of existing systems, it’s essential to bring all mechanisms to bear and use existing systems to solve as many of the user problems as possible while creating the high-fidelity person-centred data layer needed for the future. This means that there are several non-negotiables in order to sort existing data capabilities:

- Data standards must be mandatory, enforced, and future-facing. The Data (Use and Access) Bill going through the legislative process creates powers to publish, enforce, and fine. These powers should be used to create and maintain standards, certify for compliance, and embed in procurement. This should start with core standards like AboutMe and International Patient Summary, choose standards and stick to them.

- Accountability must be shared, not siloed with GPs or individual staff, which will require changes to data controllership. This means patients should have meaningful and informed control of their data.

- Interoperability must be the default, with open APIs and modern architecture, including investment in the NHS App and other national data systems to ensure the use of modern interfacing standards.

- Control must be meaningful and easy to use so patients can manage and track access.

- Legislation must align incentives and responsibilities across the system.

- Invest in data quality improvement

These nontechnological actions should improve the use of current technology while creating the space for the single patient record to break from the past and create a new approach.

Avoiding the tech mirage

The single patient record risks being yet another technology solution where technology on it’s own is not enough. The single patient record cannot be everything to everyone. There’s a need to focus on solving the non-technical barriers to get the most out of existing technologies and in parallel create a single patient record that shifts ownership, control, and data quality. Done right, it enables a care system that is more joined-up, more transparent, and more intelligent. Done poorly, it risks becoming yet another project that promises transformation but adds to the complexity of the system.

The single patient record is not just a record—it is an opportunity to realign our healthcare system around people.

Enjoyed this post? Do share with others!

You can subscribe to receive posts directly via email.

And you can get in touch via Bluesky or LinkedIn.

Transparency on AI use: GenAI tools have been used to help draft and edit this publication and create the images. But all content, including validation, has been by the author.